Harry’s Guide to Jil Sander

Everything you need to know about the understated yet progressive German luxury label.

What’s in a name? Depends on whose; if it’s Jil Sander, then it’s both a canopy bringing together a suite of ideas and a lighthouse denoting a safe stylistic shore. As a fashion house, the words signify a set of avant ideals and aesthetics that helped set fashion on a minimal course. As a name, Sander’s a magisterial, somewhat hard-to-parse artist whose output and ideas are still becoming understood. Mostly, Sander—the woman, the work—signifies minimalism: a set of cues and aesthetics that anyone interested in higher-level clothing has seen and understood and has likely bought. In many ways, Sander’s the starting point for where restraint and emotion meet. One might ask: how did such a massive canopy come out of one person? And how has such a strict stylistic definition expanded its footprint into something so big?

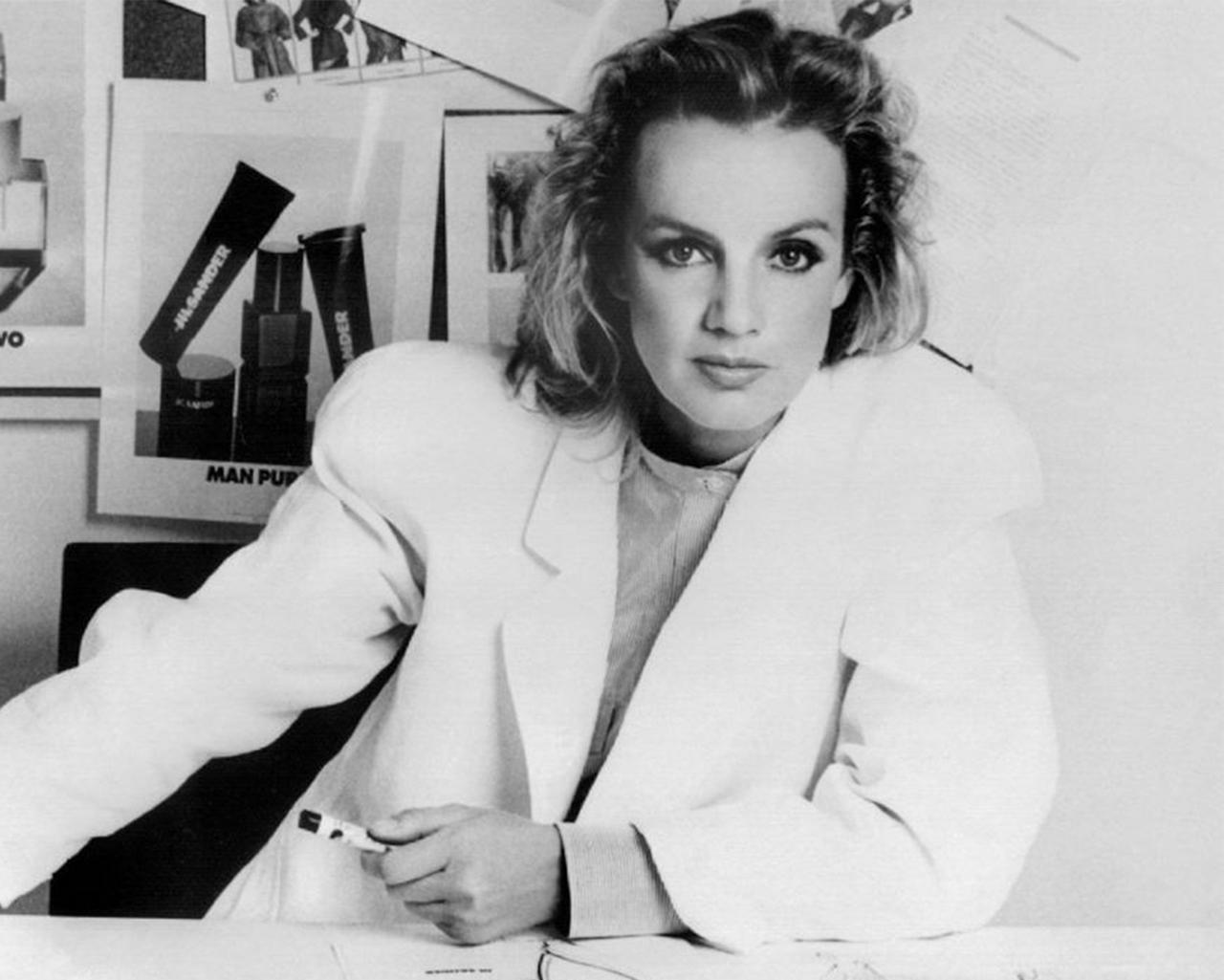

The work starts with Sander herself. Born Heidemarie Jiline Sander in northern Germany in 1943, she began styling shoots at 24 as an editor for the magazine Petra. She commenced her line soon after, using her mother’s sewing machine for early work. She had a boutique in Hamburg then, selling her clothes with others. “I was looking for more supportive ways to dress myself as a working woman,” Sander told Vogue about her start. By 1975, she was showing collections in Paris. The minimalist thread filtered out then, ahead of its time. After her early shows received negative press, she returned to Hamburg. She didn’t show again in the fashion centres until 1987. Still, her ideas—a “rapprochement of the sexes,” Sander called it, “and a more androgynous look for men and women”—were distilled from the jump.

Over the next couple of decades, Sander’s clothes progressed and refined themselves, expressing these theories more directly. Collections, all womenswear then, were designed like fine tailoring, with some flourish, but mostly attention to materials, spacing, and patterns. By the 1980s, the ideas she’d begun threading out at her boutique began to latch onto consumers, buyers and press. We associate minimalism these days with the 1990s; but it’s Sander’s work then—a counter to Armani, a flip on what was coming out of Japan—that laid the foundation.

Over time, Sander’s application of minimalism became both more subtle and distinct. A jacket one season gave way to a subtler one next; colour disappeared, shades of black and grey were distilled. Sander’s output throughout was always quite beautiful, the specificity of her early work, before the definition was standard in fashion, raises questions about what minimalism means. On a purely grammatical level, how did the minimalist outfit end up centred around loose, flouncy shapes, distinct tailoring, details and room? It certainly could have also referred to a pair of 501s with a white T-shirt, a jumpsuit, like Richard Serra used to wear, or a simple bias-cut suit. But the definition centred around designs that Sander and some of her contemporaries produced then because of the foundation they set. Pieces, she recounted in 1996, in an interview, with “a certain class… future-forward, without being futuristic.” For her, minimalism was about certain shapes, room to maneuver, and a luxuriousness in which as a designer she “leaves everything you can leave off.” Clothes were cut “with respect for the living, three-dimensional body,” she said; not for decoration. Sander’s minimalism isn’t conceptual, or even an idea—instead, clothes turned out like this because they were second to the way women—and, later men—moved. It’s the boundaries she set and the approaches she took as a designer that made the clothes sensual and got her points, about restraint and simplicity, across the quickest.

In Sander’s own words, she drew much of her inspiration from larger, more timeless themes outside fashion. “My roots are in the Bauhaus movement,” she told Vogue in 2017. The German art movement’s emphasis on “streamlined beauty, clear structures, reduction to the essential and free movement,” is a clear influence, showing up in not her work, and what came after, in later designers. It’s an idea that’s bigger than fashion, and an aesthetic that helps explain her revolutionary themes. “Functional rationality,” she said in the interview, “is only the backbone of my work.”

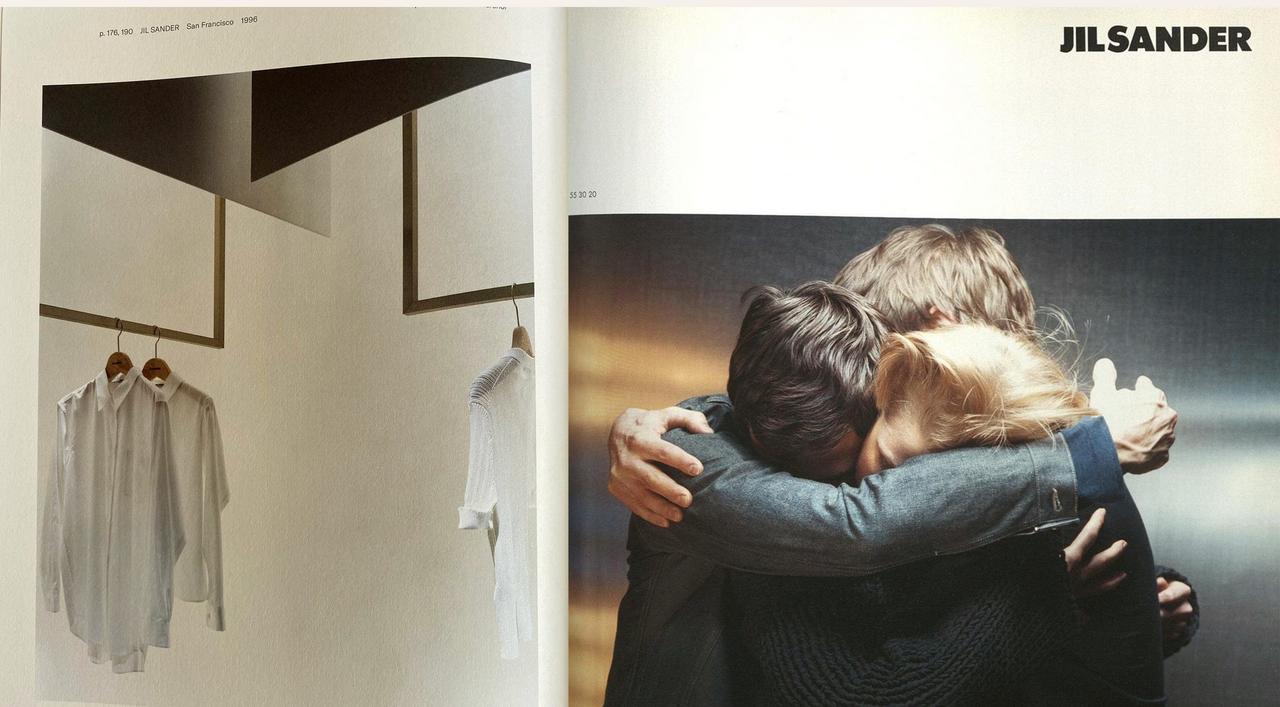

In the 1990s things at Sander began to change. Before the turn of the decade, she listed her company publicly—a first for a fashion house—on the Frankfurt stock exchange, and thereafter expanded in earnest. The decade that followed included eyewear—tasteful sunglasses, made with Alain Mikli—as well as more fragrances, which drove serious profit, all buttressing her women’s collections. Sander rolled out a Puma collaboration in 1996 and in 1997 expanded into menswear. Men’s clothing, for Sander, had always been implied through her womenswear collections if never expressly communicated. Now she was directly introducing subtle changes into the canon. Here were eternal silhouettes, tailored down to their essentials, and perfected, and slightly new. Her first collection dovetailed well with the women’s line; over the next couple of years, she’d put her own twist on staples from cardigans to shaggy trousers to suits. The best parts of the work then are as all-time as anything.

By the end of that decade, Sander was sold to the Prada group, and as ownership changed a few times, Sander herself left and came back a few times, finally departing for good in 2013. Since Sander’s first exit, for the most part, the output has remained surprisingly rich. The most revelatory work since her departure has come under Raf Simons, who steered the ship for seven years, and from the team of Luke and Lucie Meier, who are currently at the helm.

Keying into the Raf line is rewarding: the best of his collections, like much of his work, have a broader creative template and focus distinctly at youth. A menswear designer exclusively before joining Sander, his work there built off the themes Sander herself set down but expanded into a richer palette—there was colour, and lots of it—and a broader, sunnier energy. A decade plus since his ouster, the work has held up as among the most fruitful of Simons’s historic career. It challenged the brand’s minimalist ethos but remained distilled. Looking back, the clothes all look distinctly Sander.

Since 2018, Jil Sander has been helmed by Luke and Lucie Meier's husband-and-wife team. The two, who met at the Polimoda fashion school in Florence, come from opposite, if complementary, fashion backgrounds. Before acceding to Sander, Lucie worked at Marc Jacobs, Balenciaga, and, later, Dior, while Luke, a decade ago, creative directed Supreme, and then founded the luxe streetwear brand OAMC. Effectively Sander now combines a distillation of references, and paring them back (which is what streetwear, or at least Supreme, does)—with the rigorousness one comes to expect from expert fashion houses.

Collections under the Meiers have been very good. Pieces are spare or rich, sparse or regal, and distinctly luxurious. The Meiers themselves said they’re not so much reinterpreting Sander’s archive but expanding on it, contemplating the minimalist themes that the house perfected. They even, at times, depart from it: a recent collection, in AW 23, was quite loud and eclectic. There’s room here for them to do that.

Fashion is tenuous. The best ideas and houses don’t continue into eternity; in Sander’s case, there isn’t even, as per Vogue, a substantial archive of older designs. It’s not always entirely fair. But the designers who followed Sander herself have ensured that the house’s work—the well of emotions Sander got across, over decades, through natural fibres, shapes and essentiality—has lasted, and grown, beyond a person. The ideas, shocking, decades ago, are now how good clothing shakes out. It’s a testament to what Sander tapped into that the minimalism she distilled in the house when she ran it is still there and very much being continued.

Collection Highlights

Split Hem Wool Overshirt

The split overshirt, a unisex item, is, as a menswear piece, one of Sander’s more characteristic items. It’s very simple, a bit oversized, and falls very well: simple and direct. It’s a play on the Eisenhower jacket (and a few other references), taken to the hilt.

Drawstring Pleated Pants

There’s an argument that Sander’s mens trousers are among the best on the planet that can be bought off the rack—something about the slouchiness and depth of material. The key here is the drawstring, which mimics a trouser break with suspenders, as opposed to a belt. It’s otherwise almost impossible to mimic.

Midweight Wool Cardigan

Cardigans are necessary, wardrobe staples, but finding a delicate, neutral one can be tricky. This one has the right slouch and weight; it speaks to the detail the Meiers’ bring to even the layering pieces of their collections.